Plant-based proteins have several advantages for human health and the health of the planet. In fact, they are at the heart of the goals for a healthier, more sustainable diet. A few figures will help us understand the benefits they offer in the face of current and future global challenges.

Pulses (soya, split peas, chickpeas, dried beans, lentils and so on) offer a range of tastes, colours and varieties, nutritional qualities, economic and environmental benefits. They are the main dietary source of plant-based proteins and undoubtedly have a part to play in the dietary transition that is happening all over the world. Let’s analyse the figures!

The FAO estimates that global demand for protein will rise by 40% by 2030

What is more, the UN believes that agricultural production will need to increase by 70% before 2050. Why are these figures so worrying? Because we are going to face exponential growth in the world’s population. In other words, we will have to feed even more people in the future: almost 10 billion in 2050, as opposed to 8 billion today. In fact, the problem isn’t the number of mouths we need to feed, but the availability and use of the current nutritional resources.

Alongside the exhaustion of certain water reservoirs, the progressive reduction in the space available for livestock breeding, the fragility of ecosystems and biodiversity, increased global food waste, etc., our current eating patterns that focus above all on the consumption of animal protein (meat, fish, poultry, eggs etc.) are threatening global food security. This is all the more true because meat, dairy products and fish are expensive in many countries, putting them beyond the budget of many people, especially the poorest.

This is where plant-based proteins, particularly pulses, offer some major advantages:

- Pulses are an important source of protein that is more accessible and far less expensive than meat.

- They can be stored for a very long time without losing their nutritional value.

- Many pulses can adapt to droughts and precarious environments.

75g of pulses per day: the goal for a planetary diet according to the EAT-Lancet Commission (2)

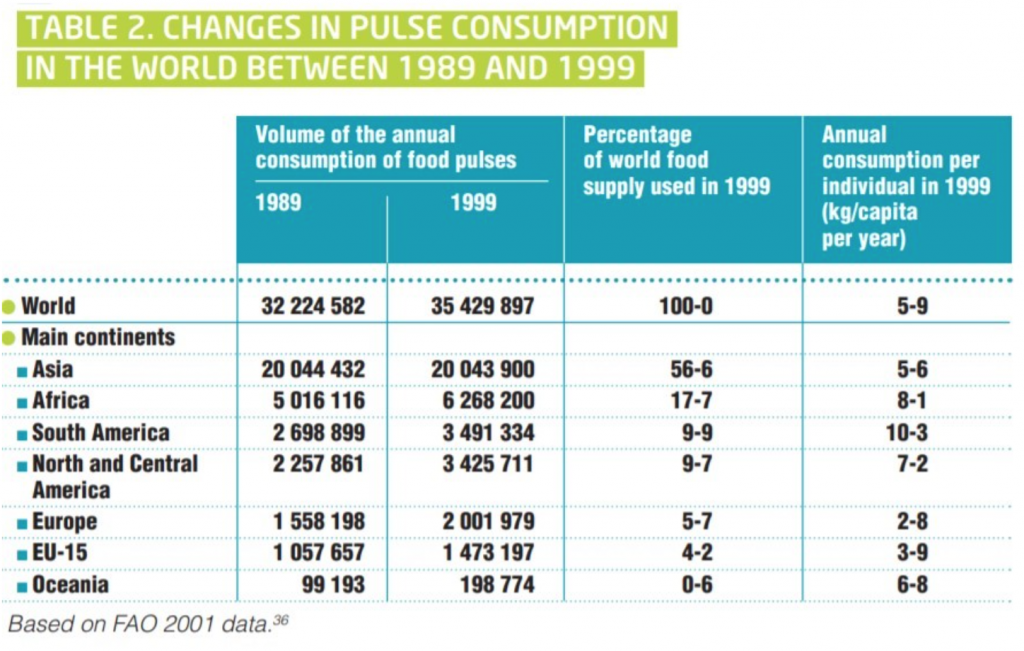

In general, dried vegetables or pulses are mainly eaten in the countries where they are grown. In the European Union, for example, few dried vegetables are eaten in comparison with other regions in the world: Europe is far behind Asia and Africa.

Source (1)

Source (1)

At a global level, the proportion of plant-based proteins consumed is insufficient in both developed and developing countries: an average of 47 g per person per day. The action recommended to tackle this deficiency is very different in these two cases:

- To increase their consumption, developed countries need to reduce and substitute the amount of animal protein they consume (40 to 60 g per person per day) to reach an ideal proportion of 50-50.

- In developing countries, the priority is to improve the quality of plant-based proteins eaten each day, since the proportion of animal protein is minimal (10 g per person per day).

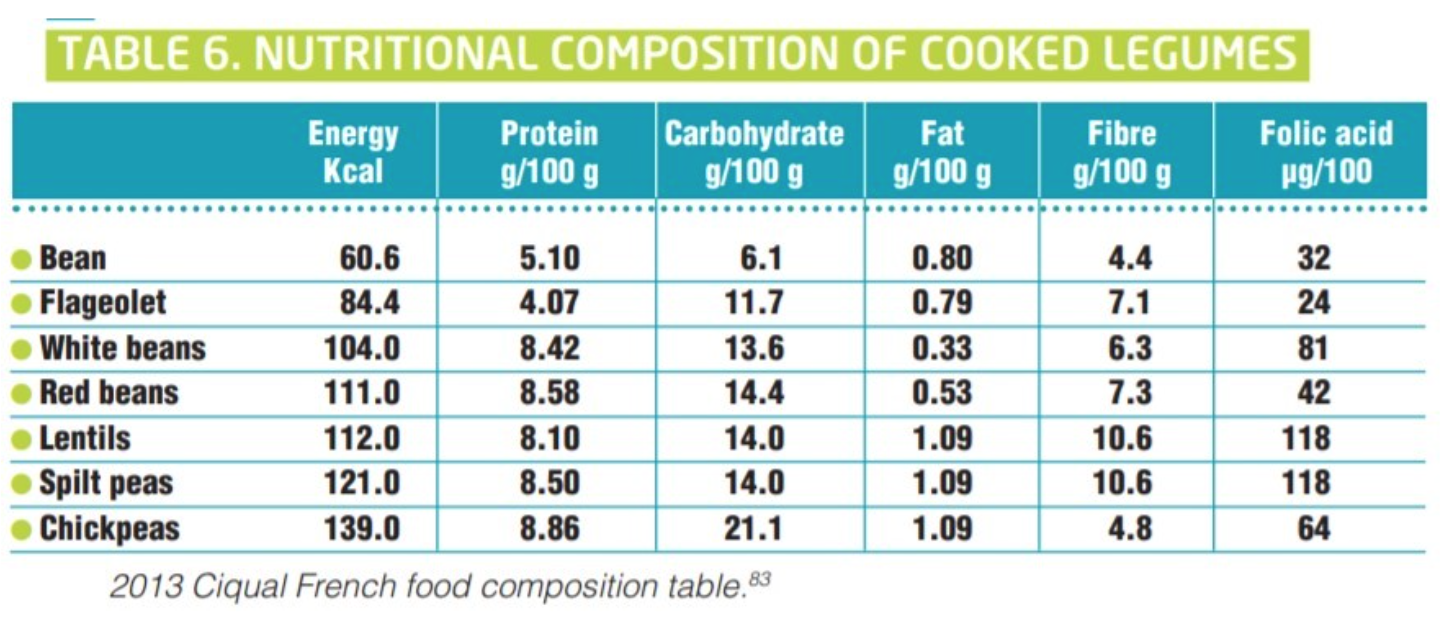

Pulses have 11 major nutritional benefits

Thanks to their unusual nutritional composition, pulses have numerous health benefits.

Here are 11 good reasons to eat them:

Source (1)

Due to this almost ‘ideal’ nutritional profile, pulses can contribute to rebalancing nutritional systems. They are also suitable for everyone, including diabetics, people trying to control their weight, pregnant women, children, people trying to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease as well as people with a gluten allergy (coeliac disease) and vegetarians (of all types, including vegans).

85 million hectares of pulses were grown worldwide in 2014, fixing between about 3 and 6 million tonnes of nitrogen (3)

This ability is linked to their capacity for symbiosis with certain types of bacteria. So they can be grown without needing any extra nitrogen. Consequently, pulses contribute to a more rational use of fertilisers, reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

But their beneficial environmental impact doesn’t stop there. When pulses are part of a crop rotation system, the risk of erosion and degradation of the soil decreases too. And pulses also increase biomass in soil and microbial activity, hence improving biodiversity.

Growing pulses in multiple crop systems thus enriches agricultural biodiversity, guarantees resilience to climate change and improves ecosystem services.

Pulses + cereals = the winning duo for plant-based proteins

What do North African couscous, Caribbean rice and beans (sometimes called “rice and peas”) and Indian lentil dhal with chapattis all have in common? All these traditional dishes combine a pulse (chickpeas, black beans or lentils) with a cereal (wheat or rice).

Foodies all around the world got the message long before the dieticians caught on: this combination is particularly rich and balanced from a nutritional standpoint, offering both energy and protein. But these foods work together in other ways as well.

Cereals are rich in sulphur-containing amino acids, but contain very little lysine. Pulses are rich in lysine, but lower in sulphur-containing amino acids. So the two sources of protein are in balance. In diets that contain little meat, the simultaneous consumption of cereals and pulses thus provides the essential amino acids our body cannot make for itself.

Carott

Carott  Artichoke

Artichoke  Vegetable garden: growing watercress

Vegetable garden: growing watercress